REPORT ON THE MEETING BETWEEN HIS HOLINESS THE DALAI LAMA AND PROFESSOR IAN HANCOCK

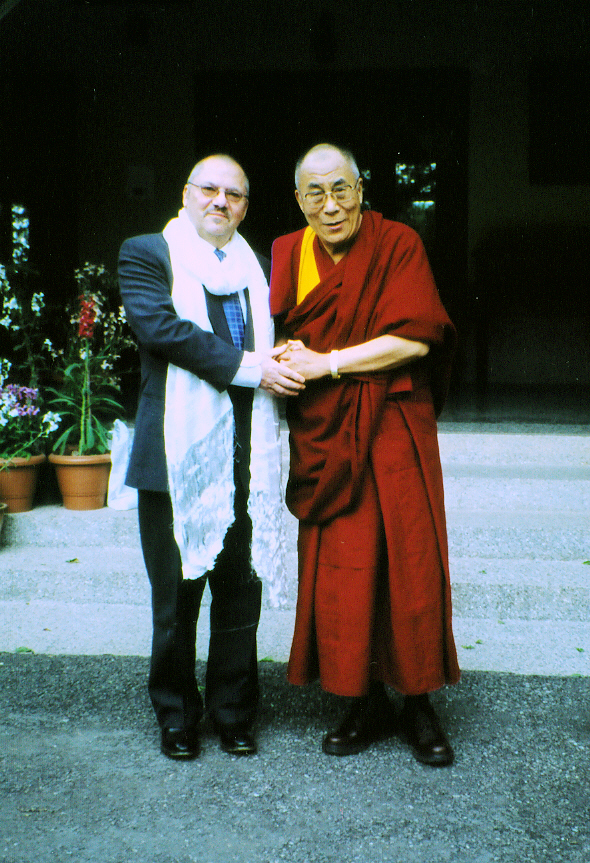

On March 12th 2003, Roma Parliament member for the United States and American Board Member of the Roma National Congress Professor Ian Hancock (o Yanko le Redjosko) had a 40-minute private meeting with the Dalai Lama at his home in Dharamsala, India, to discuss the situation of Romanies throughout the world.

Preparations for the meeting began three years ago when Dr. Hancock was invited to speak before the Anchorage chapter of The World Affairs Council in Alaska; at that event was a representative of the International Tibet Committee, who was struck by the similarities shared by the two diaspora peoples: the Tibetans and the Roma. Dr. Hancock was subsequently approached by the International Tibet Committee and preparations for the visit to India were begun.

It was necessary to be at the Tsuglag Khang, or Central Buddhist Cathedral, in Dharamsala two days before the meeting in order to discuss protocol. On the 12th, Dr. Hancock passed through security at the Cathedral’s outer office into an inner courtyard, guarded by a number of militia holding machine guns. Facing this area was the Dalai Lama’s reception room, where his two private secretaries, Tenzing Thakla and Tenzin Geshey, were waiting. His Holiness the Dalai Lama came into the room shortly afterwards.

It was immediately evident that he was familiar with Romanies. Dr. Hancock told him that as a diaspora people, with no country or government, and speaking widely differing dialects of our language, and as the principal targets of discrimination in post-communist Europe, we were facing the most difficult time in all our history. Romanies were denying their identity and assuming other ethnicities; our young people were losing the language and the culture, and turning to the worst aspects of gadjikano culture; prostitution, drugs and disease were increasingly evident. He asked the Dalai Lama how the Tibetans, as a people in exile, were able to maintain their cohesiveness in the face of the same problems.

The Dalai Lama’s first point, which he stressed emphatically, was that the strength of the people must originate in the family. The family unit must remain strong, because it was from here that real love and support—sometimes the only love and support—comes. In a hostile world where children are made to feel worthless and unloved, the family is their refuge. He said that our language must be spoken in the home, and our cultural values taught and practiced. He was particularly emphatic about keeping our language alive, and said that this was especially important for a people without a homeland.

At the same time, he stressed that while it is imperative to maintain our traditional practices, only those that have contemporary value should be passed on. Any customs or beliefs that we have which hold us back and prevent us from integrating into the bigger national society, should be abandoned. Dr. Hancock said that for some groups especially, pollution taboos were particularly strong, and served to keep children out of school and kept the barriers between Romanies and gadje firmly in place. He told the Dalai Lama that such beliefs were hundreds of years old, a legacy from India, and would be extremely difficult to change. The Dalai Lama said he understood that, and that his own Tibetan people had similar traditions, but had learnt that they were ultimately holding them back. He made a number of comparisons with the Jewish people who, until 1948, also lacked a country of their own. Dr. Hancock pointed out that Jewish people place  great emphasis on literacy and education, and have produced many scholars, while we are only now attempting to do the same.

great emphasis on literacy and education, and have produced many scholars, while we are only now attempting to do the same.

The Dalai Lama asked a number of general questions, such as how many Romanies are there in the world, are there still Romanies in India itself, or in Tibet, and what success have we had in organizing ourselves politically. Dr. Hancock told him about the efforts to create an international union, and its attendant problems. The Dalai Lama was especially enthusiastic about the Roma Parliament, headquartered in Vienna, and said that this was the best means of gaining recognition as a people. He told Dr. Hancock to come back with a delegation of several representatives of our Parliament, and that he would welcome such a group personally at any time.

Dr. Hancock asked the Dalai Lama if he would light a candle on April 8th in commemoration of Roma National Day, and he replied that he would be pleased to do that.

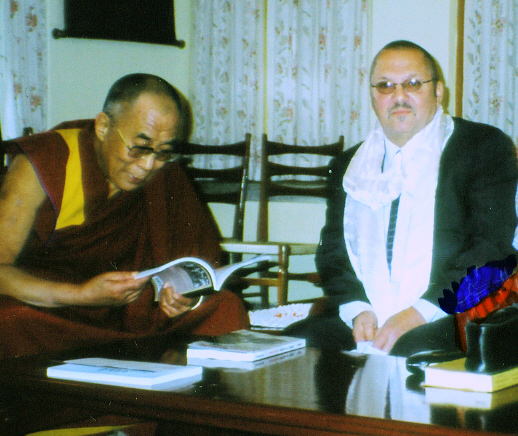

Dr. Hancock and His Holiness then exchanged katas, the white scarf given and received at such meetings, they also exchanged autographed books, and the meeting was concluded.

While in Dharamsala, Dr. Hancock also met with the Secretary General of the Tibetan Government in Exile, and expressed the solidarity of the Romani people. He has asked the Roma Parliament to issue an official statement to this effect, and supporting the movement to return Tibet to the Tibetan people.

In Chandigarh he visited the Indian Institute of Romani Studies, but since the death of its founder, Padmashri Weer Rishi, it was closed.

In Delhi he met with a number of officials at The Indian Ministry of External Affairs, with the purpose of bringing the new administration’s attention (under President Kalam) to the special place of India in Romani history, and to the ties which continue to exist. He pointed out that The First World Romani Congress was funded in part by the Indian government, and that it was the Indian government which was especially instrumental in urging the United Nations officially to recognize the Romani People. He left a copy of Madam Indira Gandhi’s Statement with them and hoped for more political and other support from the Indian government.